Saul of Tarsus / Apostle Paul

Our image of the apostle Paul is based primarily upon the Book of Acts and Paul's epistles to some of his friends and his churches. There is also extra-biblical reference to Paul in Clement of Rome's epistle to the Corinthians.

Before he became a follower of Jesus, Paul considered himself a "Hebrew of Hebrews." He came from a devout family (2 Timothy 1:3), and was a Pharisee like his father (Acts 23:6). Although he was born in Tarsus of Cilicia, he either moved with his family to Jerusalem or was sent there to study. There he was educated by the famous rabbi, Gamaliel (Acts 22:3), coming to pride himself on his heritage, discipline, and great zeal for the Law. After his conversion, Paul recognized that his "Jewishness" had become secondary to faith in Christ. However, his background as a Jewish zealot gave him credibility with some of his early Jewish audiences.

Paul's birth in Tarsus of Cilicia placed him within a great, Hellenistic center, and conferred upon him Roman citizenship. It is important to note that he did not "become" Paul after his conversion, but had from birth been "Saul Paulus of Tarsus." When he dealt with Jewish audiences he was "Saul," but when with Gentiles, he was "Paul."

As a Roman citizen, Paul possessed a coveted status that in some cases saved him from abuse (Acts 22:25–29). Later, when Paul was put on trial before the governor by members of the Jewish council, his accusers demanded that he stand trial in Jerusalem, where they planned to ambush and kill him (Acts 25:3). In order to save himself from that fate, Paul used his Roman citizenship to demand that Caesar himself hear his case (Acts 25:11), a request that ultimately brought him top Rome.

Before his conversion to Christianity, Paul saw Christians (who were mostly Jews) as a threat to Judaism. From his perspective, Christians were blaspheming God and leading Jews astray. He believed that Jesus was rightfully executed for claiming to be God. Since Jesus’ followers kept spreading the idea that Jesus was God, Paul thought Christians were sinners of the worst sort.

As a consequence, Paul became an intense persecutor of Christians. When Stephen was stoned to death for preaching the gospel, "the witnesses laid their coats at the feet of a young man named Saul . . . And Saul approved of their killing him" (Acts 7:58–8:1). After this, he asked the high priest for permission to take Christians as prisoners...

"Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats against the Lord’s disciples. He went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found any there who belonged to the Way, whether men or women, he might take them as prisoners to Jerusalem." —Acts 9:1–2

Paul's Conversion

"As he neared Damascus on his journey, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice say to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’

‘Who are you, Lord?’ Saul asked. ‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting,’ he replied. ‘Now get up and go into the city, and you will be told what you must do.’ "

—Acts 9:3-6

Paul was rendered blind by the encounter, but after days of prayer without food or water, a believer named Ananias restored his vision as directed by the Holy Spirit. Paul spent the next days with the very Christians he had come to capture, and immediately began preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ, to the amazement and confusion of both Christians and Jews. It would take time for Paul’s reputation as a Christian to overtake his reputation as a persecutor of Christians. Discussing his own conversion, Paul reported that Jesus appeared to him (1 Corinthians 15:7–8), and that Jesus had revealed the gospel to him (Galatians 1:11–16). In his letter to the Galatians, Paul asserted that the Galatians could trust the gospel he presented to them since it had come directly from God, and that the first apostles had supported it (Galatians 2:6–9).

After putting his faith in Jesus, Paul immediately began preaching publicly (Acts 9:20). He quickly built a reputation as a formidable teacher (Acts 9:22). Also, as we see from Paul’s own letters, he was highly respected in the scattered Christian communities, many of which he started himself.

Although Paul's status as a Pharisee equipped him to preach to Jews, he had a different calling. Jesus had said, "This man is my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles and their kings and to the people of Israel." This calling as an apostle to the Gentiles was corroborated by the original apostles. Paul told the Galatians that they didn’t need to follow the Law of Moses to be saved, but that they just needed to have faith in Jesus. To prove this, he told the Galatians that Peter (also known as Cephas), James, and John had nothing to add to Paul’s expression of the gospel, (Galations 2:6-9).

As an apostle to the Gentiles, not only did Paul need to engage the cultures he was trying to reach, but he had to protect new believers from the idea that they must acknowledge the obligations that Jewish Christians often tried to impose on them. He was constantly endeavoring to prove that the Gentiles didn’t need to adopt Jewish customs like circumcision in order to place their faith in Jesus and receive the Holy Spirit.

Paul established numerous churches throughout Europe and Asia Minor, and was often led to regions in which no one had evangelized before, (Paul's Missionary Journeys). Everywhere he went, Paul established new Christian communities and helped the fledgling believers develop their own leadership. He corresponded with these churches regularly and visited them as often as he could. Occasionally, they supported him financially so that he could continue his ministry elsewhere (Philippians 4:14–18, 2 Corinthians 11:8–9).

Jesus promised his disciples that they would receive power through the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:8). Many miracles are attributed to the apostles, and scripture shows that Paul was similarly empowered. Among the signs that he performed were the following:

- Made a sorcerer go temporarily blind (Acts 13:11)

- Cast out a spirit that was annoying him (Acts 16:16-18)

- Healed people and cast out spirits through items he touched (Acts 19:11–12)

- Healed a man who had been lame since birth (Acts 14:8–10)

- Was bitten by a venomous snake with no ill effect (Acts 28:3-5)

- Healed a man with fever and dysentery (Acts 28:8)

- Resuscitated a young man named Eutychus (Acts 20:9-12)

Paul's most important contributions were through his role in spreading the gospel to non-Jewish communities. While he was not the only apostle to do so, he quickly became known as the "apostle to the Gentiles." The other apostles agreed that this was his role (Galatians 2:7), and should be the focus of his ministry.

Early Christianity was often thought of as a Jewish sect because most Christians were also Jewish and the new faith was built upon Jewish teachings and beliefs. Many of its early adherents still followed Jewish customs and rituals established in the Law of Moses. For Paul, the apostles, and the early Christians, the Law (and specifically, circumcision) was one of the greatest theological issues of the time, as first-century Jews had grown up believing the Law was central to their identity as God’s chosen people. Many struggled to fully grasp that Jesus rendered the Law obsolete (Hebrews 8:13).

Paul told Gentile Christians not to worry about circumcision, and in Acts 15, the apostles met with Paul and Barnabas to officially settle the matter. Peter argued that God hadn’t discriminated between Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians in the giving of the Holy Spirit. He also asserted that in the entire history of Judaism no one had been able to keep the Law, making the placement of that burden upon the Gentiles a mistake (Acts 15:7-11). James summarized the groups decision by stating...

"It is my judgment, therefore, that we should not make it difficult for the Gentiles who are turning to God. Instead we should write to them, telling them to abstain from food polluted by idols, from sexual immorality, from the meat of strangled animals and from blood. For the law of Moses has been preached in every city from the earliest times and is read in the synagogues on every Sabbath."

Acts 15:19–21

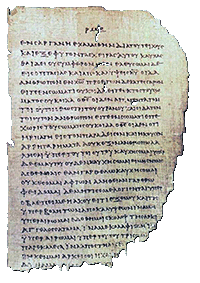

The Apostle Paul is traditionally considered the author of 13 books of the New Testament. The books attributed to him include:

Romans* 1 Corinthians* 2 Corinthians* Galatians* Ephesians* Philippians* Colossians* 1 Thessalonians* 2 Thessalonians* 1 Timothy* 2 Timothy* Titus* Philemon*

These books are actually letters, ("epistles") that were written to churches Paul established and people he encountered on his missionary journeys. The letters reference many of the events recorded in Acts, allowing scholars to construct clearer timelines of Paul’s life and ministry.

Not everyone agrees that Paul wrote all of these letters. Most scholars do agree that Paul did write seven of them: Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon. But for some, the remaining six letters have led scholars to debate whether or not they can be attributed to Paul. Many Christians would be surprised to learn that these academic debates are even happening, because these letters are all signed by Paul. However, scholars argue that these epistles are actually pseudepigrapha. Some pseudepigrapha are harmless and produced out of convenience, (such as a student writing on behalf of a teacher, with the approval and authority of the teacher). Others, like many of the Gnostic gospels, were blatant forgeries written to advance a theological position.

Almost all scholars today agree that Paul didn’t write Hebrews, and the true biblical author remains unknown. Early Christian writers even suggested possible alternative authors. Tertullian (c. 155–240 AD) proposed that it was written by Barnabas. Hippolytus (c. 170–235 AD) believed it was authored by Clement of Rome. While we may never know who really wrote Hebrews, most are confident that it wasn’t Paul.

On many of Paul’s journeys, he traveled by boat. Scripture suggests that he was shipwrecked at least three times, (2 Corinthians 11:25).There’s no other record of these wrecks in the epistles or in Acts, but Acts 27 does record a fourth shipwreck in more detail. On Paul’s way to trial in Rome, his boat encounters a brutal storm and is finally wrecked on a sand bar off of Malta, (See "To Caesar" for details).

Murder Plots

Once his conversion had taken place and Paul had begun to preach the gospel, he angered many zealous Jews, leading some to want him dead. Over the years of his evangelizing, numerous attempts were made on his life.

In Damascus following his conversion , Paul's preaching prompted some to watch the city gates day and night with plan to kill him as he left. He was secreted out of the city and away from the threats by brothers who lowered him in a basket through an opening in the city wall,(Acts 9:23-25).

After leaving Damascus, Paul went to Jerusalem and tried to join the disciples there. When he started debating with Hellenistic Jews they tried to kill him, leading other Christians to take him to Caesarea, and from there, home to Tarsus (Acts 9:26–30).

Paul and Barnabas spent a long time in Iconium, and the city was divided: some people supported them, and others hated them. Jews and Gentiles alike plotted to stone them, and when Paul and Barnabas found out, they fled to Lystra (Acts 14:4–6).

After Paul healed a man in Lystra, people thought he and Barnabas were gods, and attempted to sacrifice to them. However, some Jews from Antioch and Iconium convinced this crowd to actually stone Paul. They left him outside the city gate, thinking that they had killed him. Happily, he was still alive, and he and Barnabas left (Acts 14:8–20).

In Jerusalem, Paul insulted the high priest and started an intense theological debate between the Sadducees and Pharisees. Following this, a group of more than 40 men took a vow not to eat or drink until they had killed Paul (Acts 23:12–13). Their plan was to have a centurion send Paul to the Sanhedrin for questioning, and then kill him on the way. When someone warned the centurion of the plan, he instead had his soldiers to take Paul to the governor in Caesarea.

Years later, and still in Caesarea, Paul was still being held prisoner under the new proconsul named Porcius Festus. Paul’s accusers requested that Paul be sent back to Jerusalem "for they were preparing an ambush to kill him along the way," (Acts 25:3). Festus refused, and told them to make their case in Caesarea, leading Paul to use his privilege as a Roman citizen to appeal to Caesar.

When Paul was first imprisoned in Caesarea, he made his appeal to Governor Felix, then waited two years in prison with no progress. Felix was succeeded by Porcius Festus, who, after hearing Paul defend himself, asked if Paul would be willing to stand trial in Jerusalem. Tired of his case dragging on to appease his Jewish accusers, Paul claimed his right as a Roman to appeal to Caesar. This may have been a strategic move on Paul’s part as he wished to testify about Christ to the leaders of the Roman empire.

By appealing to Caesar, Paul forced Festus to send him to Rome to await trial. When he finally arrived, he was allowed to live by himself, with a soldier to guard him, (Acts 28:16). Here, Paul preached freely to the Jews in Rome for two years and some believe this may be when he wrote his letter to the Philippians, (Philippians 1:12–13).

The Book of Acts ends with Paul under house arrest, and it is not known if Paul was ever released from house arrest. Whether or not Paul made a fourth missionary journey to Spain largely depends on whether he was imprisoned in Rome once or twice.

The Bible doesn’t tell us how Paul died, but numerous early church fathers wrote that he was beheaded, probably by emperor Nero, (placing it sometime before 68 AD). Clement of Rome provided the earliest surviving record of Paul’s death in his letter to the Corinthians. In it, he mentioned that Paul and Peter were both martyred. In 200 AD, Tertullian wrote that Paul’s death was like John the Baptist’s (1.e. decapitation), and other early Christian writers provided some additional details, including the fact that he was killed in Rome and buried along the Ostian Way.

In 2002, archaeologists found a large marble sarcophagus near the proposed burial location Jerome and Caius had described. Inscribed on it were the words, "PAULO APOSTOLO MART," (i.e. Paul apostle martyr). While no one opened the sarcophagus, probes were used to obtain material for carbon dating. It was subsequently estimated that the remains inside were from the first or second century. The Vatican claims these are in fact the remains of Saint Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles.