Ancient Israel

The origins of Ancient Israel trace back to the early second millennium BCE, with the journey of Abraham, a Semitic patriarch, from Ur in Mesopotamia to the land of Canaan. This divinely driven migration laid the foundation for the establishment of a new lineage. Abraham's descendants, particularly Isaac and Jacob, further solidified their ties to Canaan, with Jacob later being named Israel, giving rise to the term "Israelites" for his descendants.

After famine in the land of Canaan, the Israelites found themselves in Egypt around the 13th century BC. Initially welcomed due to the actions of Joseph, one of Jacob's sons, they later faced oppression and were subjected to slavery. This period of bondage culminated in one of the most pivotal events in Israelite history: the Exodus.

Led by Moses, the Israelites embarked on a decades-long journey through the desert, during which they received the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, a key to their emerging religious identity. Upon their return to Canaan, around the late 13th to early 12th century BCE, the Israelites faced the challenge of settling into a land inhabited by various antagonistic tribal groups. Under the leadership of Joshua, they embarked on a series of military campaigns. Through a combination of warfare, alliances, and settlements, the Israelites carved out territories for the twelve tribes, laying the groundwork for the nation's future political and cultural development.

Following their settlement in Canaan, the Israelites entered a distinct phase in their history, commonly referred to as the Period of the Judges. This spanned from around the 12th to the early 10th century BC. During this era, Israel did not have a monarchy, but instead, leadership was often provided by charismatic individuals known as judges. These leaders were chieftains or military leaders who rose to prominence in times of crisis, rallying tribes to defend against external threats.

Notable among the judges were Deborah, a prophetess who led the Israelites to victory against the Canaanite king Jabin; Gideon, who successfully defended Israel against the Midianites; and Samson, whose legendary strength and tumultuous relationship with the Philistines have been immortalized in numerous stories.

The Period of the Judges was also a time of tribal fragmentation and infighting, with the Israelites often lapsing into idolatry and straying from their covenant with God. This pattern of apostasy, oppression by neighboring groups, repentance, and deliverance by a judge became a recurring theme. The Philistines, in particular, emerged as a formidable adversary during this era, leading to frequent clashes.

The transition from the Period of the Judges to a centralized monarchy was a pivotal shift in the political landscape. The so-called, "United Monarchy," spanned the 10th century BCE and saw the rise of Israel's first kings: Saul, David, and Solomon. Saul, from the tribe of Benjamin, emerged as Israel's inaugural king around the mid-10th century BCE.

As tensions between Saul and David escalated, a tragic sequence of events led to Saul's downfall and eventual death on the battlefield. David, having garnered significant support during Saul's reign, assumed the throne and embarked on a series of military campaigns that expanded Israel's borders and influence. His most notable achievement was the capture of Jerusalem around 1000 BCE, which he established as the political and religious capital of the united kingdom.

Under David's leadership, Israel enjoyed relative peace and prosperity. Solomon, David's son, succeeded him and is best remembered for his wisdom and monumental building projects. The most iconic of these was the construction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, which became the central place of worship for the Israelites and housed the Ark of the Covenant. Solomon also forged alliances through marriage and diplomacy, enhancing Israel's regional stature. However, his extravagant spending on building projects and the introduction of foreign cults, due to his many foreign wives, led to internal discontent.

Following Solomon's death around 930 BCE, the kingdom began to unravel. Rehoboam, Solomon's son, ascended to the throne, but his early decisions ignited widespread discontent, culminating in a significant revolt led by Jeroboam, an official from the northern tribes. The outcome was a profound split, with the northern ten tribes establishing the Kingdom of Israel, and the southern tribes, primarily Judah and Benjamin, forming the Kingdom of Judah with Jerusalem as its capital.

The Kingdom of Israel, with its capital initially in Shechem and later in Samaria, saw a succession of dynasties and rulers. Jeroboam, its first king, set up alternative religious centers in Bethel and Dan, partly to counteract the allure of the Temple in Jerusalem. Over the years, Israel grappled with internal power struggles and external threats, especially from the expanding Assyrian Empire. Prophets like Elijah and Elisha played significant roles during this period, challenging the Israelite kings and advocating a return to the worship of Yahweh. The Kingdom of Judah, though smaller, benefited from the religious and administrative structures established during the United Monarchy. The Davidic line continued to rule, with some kings, like Hezekiah and Josiah, noted for their religious reforms and efforts to centralize worship in the Jerusalem Temple.

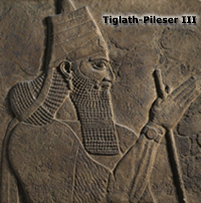

The fate of the two kingdoms diverged dramatically in the late 8th century BC. The Kingdom of Israel, after years of political instability and Assyrian pressure, fell to the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III and later Shalmaneser V. The culmination of these campaigns was the siege of Samaria by Sargon II around 722 BCE, leading to the exile of a significant portion of the Israelite population and the end of the northern kingdom. The Kingdom of Judah eventually faced the rising power of Babylon. Despite periods of allegiance, tensions reached a breaking point in the early 6th century BCE. Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon laid siege to Jerusalem and brought about the city's fall in 586 BC. The destruction of the Temple occurred along with the beginning of the Babylonian Exile for the Judeans.

With the city's destruction and the subsequent exile of a significant portion of the Judean population to Babylon, the Jews' communal and religious life was disrupted. Without the centralizing force of the Temple, synagogues began to emerge as places of worship, study, and community gathering. The role of scribes and scholars became increasingly important, leading to the compilation and editing of various biblical texts.

In 539 BC, changes developed with the rise of the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great. The Persians, having conquered the Babylonians, adopted a more benevolent approach to governance. Cyrus issued a decree allowing various exiled communities, including the Israelites, to return to their homelands and restore their places of worship. This edict marked the beginning of the end of the Babylonian Exile.

The return to Judah occurred in waves over several decades and was challenging. The land was in ruins, and the task of rebuilding was daunting. Under leaders like Zerubbabel, Joshua the High Priest, and later Ezra and Nehemiah, the Israelites embarked on projects to rebuild the Temple and the walls of Jerusalem.

The subsequent centuries saw Judah, (now commonly referred to as Judea), fall under the influence or direct control of various empires. The Persians were succeeded by the Greeks following Alexander the Great's conquests in the late 4th century BCE. After his death, his empire fragmented, and Judea found itself caught between the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt and the Seleucid dynasty in Syria. By the 2nd century BCE, under the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, tensions reached a boiling point. The policies of Antiochus, which included Hellenization efforts and the desecration of the Temple, sparked a revolt led by the Maccabean family. Their rebellion resulted in the re-dedication of the Temple, an event commemorated by the Jewish festival of Hanukkah, and the establishment of the Hasmonean dynasty.

The Hasmoneans were initially priestly leaders, but eventually adopted the title of king and expanded the borders of Judea. However, internal conflicts and the rising power of Rome in the Mediterranean world weakened their hold. By the mid-1st century BCE, Rome had established its dominance over Judea, first through client kings like Herod the Great, and later through direct Roman governors.

Herod greatly expanded the temple structures, and throughout this "Second Temple Period," Judea experienced significant cultural and religious developments. Hellenism led to debates about assimilation and identity. Sectarian groups, such as the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots, emerged, each with distinct interpretations of Judaism and visions for the future.

Following Herod's death, his kingdom was divided among his sons, but Roman intervention became more direct over time. By 6 AD, Judea was incorporated as a province of the Roman Empire, governed by Roman procurators. This shift in governance brought with it increased taxation and Roman legal practices, often at odds with Jewish customs and laws. The cultural and religious differences between the Roman rulers and the Jewish people led to growing tensions.

The situation reached a breaking point in 66 AD when widespread revolts erupted against Roman authority, initiating the First Jewish-Roman War. Over the next four years, the Romans, under generals Vespasian and his son Titus, waged a brutal campaign to suppress the rebellion. The climax came in 70 AD when Roman legions besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the city and its Temple. This catastrophic event had profound implications for Jewish identity and practice, signaling the end of the centralized cultic worship associated with the Temple.

The center of Jewish life and scholarship gradually moved away from Judea, laying the groundwork for the Jewish diaspora that would spread across the Mediterranean and beyond. The Pharisaic tradition, emphasizing study and interpretation of the Torah, evolved into Rabbinic Judaism. This new form of Judaism, with its emphasis on the oral tradition and communal study, would play a pivotal role in preserving Jewish identity and beliefs in the centuries to come.