Crucifixion of Jesus

Methods employed by the Romans in crucifixion certainly varied at times, particularly if the punishments were dealt out in large numbers at time of war. The methods may well have varied between regions, evolved over time, or even depended upon the social status of the victim and the crime he allegedly committed.

Specific teams of soldiers were assigned to crucifixion duty with each comprised of at least 4 legionnairies and one supervising centurion. It was the centurion's obligation to oversee the entire process and to finally see, and attest to, the death of the victim. Were the condemned to survive the cross, the centurion's life would be forfeit.

As will be shown below, certain aspects of the execution process became standard for most cases. However,variations to the details were allowed at the whim of the centurion, and the timing of the victim's death might also, at times, be determined by this presiding officer.

Since one purpose of the process was the humiliation of its victim, soldiers not infrequently included varied and bizarre tortures as a part of the execution.

Flavius Josephus (37-c.100CE) wrote of the hundreds of Jewish prisoners crucified at Jerusalem in 70 AD, during an uprising against the Romans...

Lucius Anneus Seneca (4BC-65AD) recorded another mass crucifixion and noted:

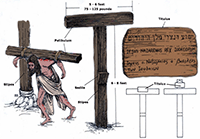

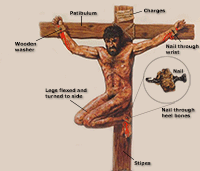

Types of Crosses

Historically, crucifixion was accomplished on a wide variety of apparatuses. The simplest "cross" was a single stake or pole in the ground, (in Latin, "crux simplex"), to which the victim would be lashed or nailed. This form was likely used in far antiquity by the Assyrians and Persians. In Roman times, and certainly in the case of Jesus' crucifixion, a multi-beam cross was employed that was comprised of a vertical post ("stipes") to which a horizontal beam, ("patibulum"), was affixed. This allowed for the stipes to be firmly and permanently planted at the site used for crucifixions, while the cross-beam (patibulum) would be brought to the site at the time of the execution.

This was practical on many levels. First, a full, 2-part cross would weigh in excess of 300 lbs, making it impossible for the victims to carry. Secondly, wood was scarce in Jerusalem, making the re-use of execution stakes (stipes) quite logical. As the first-century Jewish historian Josephus noted, wood was so scarce in Jerusalem during the first century A.D. that the Romans were forced to travel ten miles from Jerusalem to secure timber for their siege machinery.

Some in the modern era have suggested that Christ was, in fact, nailed to a pole, because of the Bible's use of the Greek word, "stauros," (which is most commonly translated as "stake" or "pole"). However, the descriptions by historians of victims with "outstretched arms," together with other records of the condemned carrying their "crosses" on their shoulders strongly suggest that a multi-part torture instrument was employed. Further corroboration of this is the many reports of crucifixion victims living for days before succumbing, which most acknowledge would be impossible for anyone hanging by the arms from a vertical pole.

Journey to the Cross

Following the terrible beating he endured, the condemned was often made to "carry his cross" to the place of execution. The cross-beam (patibulum) was placed over his shoulders and lashed to his outstretched arms with ropes. That this practice was common is corroborated by Greek biographer, Plutarch (AD 46-120), who stated "every criminal who goes to execution must carry his own cross on his back." However, it also appears that this was not a universal rule. The Laws of Puteoli which regulated how crucifixions were to be carried out, stated that carrying the patibulum was optional—to be decided by the contractor in charge of the crucifixion: "If the contractor wants the condemned to bring the patibulum to the cross, the contractor will have to provide the wooden posts, chains, and cords for the floggers and floggers themselves." The floggers were used to goad the victim to continue moving to the place of execution.

The path to the place of crucifixion was laid out in such a way as to guarantee a large crowd of onlookers. These people would commonly spit upon the condemned and pelt him with stones and other debris. The processional was led by a complete Roman military guard, headed by a centurion. One of the soldiers carried a sign on which the condemned man’s name and crime were displayed. Later, this would be attached to the top of the cross.

Misconception?The place of execution was standardly outside the city walls in a place of prominence along a main road. The Roman historian Tacitus records that the city of Rome had a specific place for carrying out executions, situated outside the Esquiline Gate, and also had a specific area reserved for the execution of slaves by crucifixion. A similar situation most likely existed in Jerusalem of the 1st century. That the execution of Jesus took place at "Golgotha," or "the place of the skull," certainly suggests that this was a place used recurrently for executions.

See Video

Crucifixion Methods

Once outside the city walls and at the place for execution, the victim, (if previously clothed), was stripped naked.

Misconception?By law, the victim was offered a bitter drink of wine mixed with myrrh (gall) as a mild pain reliever. The criminal was then thrown to the ground on his back with his arms outstretched along the crossbar. The hands could be nailed or tied to the crossbar, but nailing apparently was preferred by the Romans. Because of the preciousness of the iron nails, they were often retrieved at the end of the execution in order to be re-used. (Interestingly, objects used in the crucifixion of criminals, such as nails, were sought as amulets that were perceived to have medicinal qualities.)

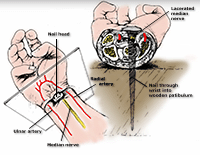

Controversy has long surrounded the method used for nailing the hands, and whether in fact, the "hand" in our sense of the word was involved at all. The idea of nails through the palms grew widespread as the result of medieval and renaissance artistic depictions of the crucifixion. However, the Greek word ("χείρ") interpreted in scripture as "hand" is known to refer to any portion of the upper extremity below the elbow. Famously, the French physician, Pierre Barbet (1884–1961) the chief surgeon at Saint Joseph's Hospital in Paris, performed experiments by crucifying cadavers, and concluded that nails in the palms would not support the victim's weight. Barbet proposed that the nails were placed through the Destot's space on the side of the wrist away from the thumb, ("ulnar" side).

Others opined that the nails had actually been placed through the wrist (the distal-volar forearm)and perhaps traversed the space between the radius and ulna, (bones of the forearm). However, subsequent work has suggested that a trans carpal fixation would be strong enough to support the victim, and that trans-palmar nailing would even be possible if reinforced with ropes around the forearm.

Whether placing the nail through the carpus or between the bones of the forearm, the Roman executioners were careful to avoid the radial and ulnar arteries, (see diagram). As a result, blood loss would be modest, helping to prolong the victim's agony. However, while the central position of the nail helped to spare those arteries, it very likely insured damage or even severance of the median nerve. This would partially paralyze the hand, and even more critically, produce lancinating pain in the hand and down the arm, particularly when the victim changed position on the cross.

Once fixed to the patibulum, the condemned man would be raised by 3-4 soldiers and the crossbeam fixed to the stipes (stake) with ropes and nails. This most likely left the victim's feet a foot or two off the ground. Although the legs could have at times been tied to the stipes with rope, the Roman preference was again to use nails.

Several methods were employed. In some cases the feet were nailed to a footrest ("suppedaneum"), while in others they were nailed directly to the front of the post. To accomplish this, flexion of the knees may have been quite prominent, and the bent legs may have been rotated outward.

Several methods were employed. In some cases the feet were nailed to a footrest ("suppedaneum"), while in others they were nailed directly to the front of the post. To accomplish this, flexion of the knees may have been quite prominent, and the bent legs may have been rotated outward.

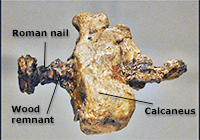

The only archeological evidence we have for someone crucified in the first century is the remains of a young man named Jehoḥanan ben Ḥagqol whose bones were found in a family ossuary in Jerusalem (1968). It is known that he was crucified because a nail was still in his right calcaneus (heel bone). When the nail was originally inserted it may have hit a knot of wood or another nail in the stipes causing the tip of the nail to bend.  As a result, it could not be removed and was buried with the victim. The position of the nail indicates that Jehohanan’s feet were nailed on either side of the upright beam of the cross, a position also depicted in the Puteoli crucifixion graffito of Alkimilla. There was no evidence in the case of the Jehoḥanan remains that the bones of the arms or hands were nailed to the cross, so he may have been tied to the patibulum. To further reinforce fixation of the hands (and feet) to the cross and prevent the victim ripping the limb free, nails were usually first driven through wooden "washers" before entering the victim and the wood of the cross.

As a result, it could not be removed and was buried with the victim. The position of the nail indicates that Jehohanan’s feet were nailed on either side of the upright beam of the cross, a position also depicted in the Puteoli crucifixion graffito of Alkimilla. There was no evidence in the case of the Jehoḥanan remains that the bones of the arms or hands were nailed to the cross, so he may have been tied to the patibulum. To further reinforce fixation of the hands (and feet) to the cross and prevent the victim ripping the limb free, nails were usually first driven through wooden "washers" before entering the victim and the wood of the cross.

Once the crucifixion victim was fixed to the cross, a slow and agonizing waiting game began. The sign with the victim's name and charges was attached to the cross. The soldiers and the civilian crowd often taunted and jeered the condemned man, and if he had arrived at the place of execution with any clothes, the soldiers customarily divided these up among themselves. Not uncommonly, insects would light upon or burrow into the open wounds or the eyes, ears, and nose of the helpless victim, and birds of prey would tear at his wounds. The length of survival generally ranged from three or four hours to several days and would depend upon the health and age of the victim, the position in which he was fixed to the cross, the severity of his scourging and the seasonal outdoor temperature, (see Death of Jesus).