Agriculture was of critical importance to the people of Israel, and as a result, metaphors relating to it are found throughout the bible. Students of the Word who are unfamiliar with the life and methods of the ancient farmer will find this review of potential value.

In Palestine, ploughing is done after the early rains have softened the earth (Psalm 65:10). These rains usually come in later October or early November. If the rains do not come then, a farmer must wait for them before he can plough the ground. Job said, "They waited for me as for the rain." (Job 29:23). Jeremiah said that when there was no rain,"the ploughmen were ashamed, they covered their heads." (Jer. 14:4).

The farmer readies things for ploughing after the first rain begins. He makes sure that his plough is in good repair and may need to cut and point a new goad to use in prodding his team of oxen. He will also see to it that his yoke is smooth and fits the necks of the animals well. An poorly-shaped or heavy yoke would irritate his animals. (The Lord Jesus spoke of "the easy yoke" promised to His followers, Matt. 11:30). When the ground has been sufficiently softened by the rain, the ploughing can begin.

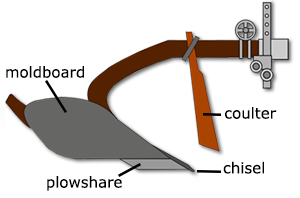

One Palestinian plough is made up of two wooden beams that are joined together and at the front end are hooked to a yoke. At the rear it is fastened to a crosspiece, the upper part of which serves as the handle while the lower part holds the iron ploughshare or colter. Even today many use such devices in Middle East lands. Bible writers often mention iron ploughshares (1Sam. 13:20, etc.). These could be changed without much work into swords for warfare. Thus the prophet Joel said: "Beat your ploughshares into swords" (Joel 3:10), which was exactly the reverse of what was suggested by both the prophets Isaiah and Micah in predicting a future, Golden Age (Isa. 2:4; Micah 4:3).

The yoke is a rude stick that fits the necks of the cattle who are to draw the plow. Two straight sticks project down each side, and a cord at the end of these sticks and underneath the animal's necks holds the yoke to their necks. Such yokes of wood are often spoken of in the Scriptures (Jer. 28:13).

A goad, commonly used in Bible times, was a wooden rod varying in length from five to seven feet that had a sharp point at one end. Using this the farmer could hurry the progress of slow-moving animals. It was such an ox-goad that was used by Shamgar in slaying six hundred Philistines (Judges 3:31). At the time of the conversion of Saul of Tarsus Jesus compared Saul's conviction to the pricks of an oxgoad: "It is hard for thee to kick against the goad," (Acts 26:14).

The Hebrews used the term oxen to mean both sexes of the animal, cows being used as well as bulls (with bulls castrated). The law specifying that a heifer be used for sacrificial purposes specified that it be one "upon which never came yoke" (Num. 19:2). The law of Moses also forbade the practice of ploughing with an ox and an ass yoked together (Deut. 22:10). Much later, the Apostle Paul spoke of "the unequal yoke" when discussing the partnership between believers and unbelievers (2Cor. 6:14)

There are various kinds of grain used in Palestine. The word "corn," used in English translations of the Bible is actually the family name for cereal grains, (the crop we call corn was unknown to Bible writers). The two main grains cultivated in ancient Palestine were wheat and barley. There is one mention in the Old Testament of the use of millet (Ezek. 4:9).

The farmer usually carried seed to his field in a large sack on the back of his donkey, and used a leather bag carried under his arm that was replenished with seed from the sack. Generally, the seed would be scattered on the ground and then be covered over by the ploughing. Often the sower would walk along scattering seed while one of his family or a servant would follow with the plough. The Biblical word "to sow," as used in the Pentateuch (Gen. 26:12; Lev. 25:3) means "to scatter seed."

Grainfields in Palestine are largely dependent upon the rain that falls. No rain falls from May to September. It is the October/early November rain that is the signal to begin ploughing and planting. The Bible also speaks of a latter rain, which ordinarily falls in March and April, and it is this rain that is important to the maturing the grain crops. Heavy winter rains often come in late December and during January to February. The prophet Joel mentions all three of these rains: "And he will cause to come down for you the rain, the former rain, and the latter rain in the first month" (Joel 2:23). The winter rain is a heavy rain that falls in winter months, but the rainy season starts with the "former rain" in the fall and ends with the "latter rain" in the spring. Barley is harvested in April and May and the wheat in May and June.

The ripened grain was cut with a sickle. Sickles were made of flint, which was abundant and cheap. In later periods there were some made of bronze or of iron. The flint was at first set in the jaw-bone of an animal, or in a curved piece of wood. The prophet Joel commands: "Put ye in the sickle, for the harvest is ripe" (Joel 3:13). The cut grain was gathered on the arms and bound into sheaves. Psa. 129:7 makes reference to the mower filling his hand, and the binder of sheaves filling his bosom, and Joseph in his dream saw "binding sheaves in the field" (Gen. 37:7).

Although there were instruments sometimes used for people to perform manual threshing of grain, the most common method used by the Jews was to have oxen driven over the grain in order to thresh it. The animals were turned over the layer of grain as it lay upon the threshing floor, and their hoofs did the work of threshing. The Hebrew verb 'to thresh' is "doosh," which suggests "to trample down," or "to tread under foot" (Job 39:15; Dan. 7:23).

Winnowing was accomplished by the use of either a broad shovel or of a wooden fork with bent prongs. With this instrument, the mass of chaff, straw, and grain was thrown against the wind. When the unseparated grain and straw are thrown into the air, the wind causes the material to fall as follows: the heaviest part (the grain) falls beneath the fan. The straw is blown to the side into a heap, and the lighter chaff and the dust are carried beyond into a flattened windrow. This gave to the Psalmist his simile: "The ungodly are not so, but are like the chaff which the wind driveth away" (Psa. 1:4). The chaff is burned, as was made clear when John the Baptist said: "Whose fan is in his hand, and he will throughly purge his floor, and gather his wheat into the garner; but he will burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire" (Matt. 3:12; Luke 3:17).